Performance Measurement

Performance measurement typically drives much of the way a large company works. We talked extensively in this book about how accounting profits or profit growth as a sole performance metric doesn’t lead to value creation. Supplementing profits with ROIC and revenue growth is a step in the right direction to ensure that the profits a business earns are actually creating value, not simply over-consuming capital that another company could better deploy. However, profits, ROIC, and revenue growth are backward looking. They don’t tell you how well the business is positioned for future growth and ROIC improvement.

One company we know had a particular business unit that consistently recorded growing profits and high levels of ROIC for about four years. Since the unit’s reported financial results were so good, the executives at the corporate headquarters didn’t ask many questions about the drivers of the unit’s profits – until it was too late. It turned out that the unit was driving profits by raising prices and cutting marketing and advertising expenditures. Higher prices and reduced advertising created an opening for competitors to take away market share, which they did. So while profits were rising and ROIC was high, market share was declining.

The next thing the company knew, it couldn’t raise prices anymore, and market share kept falling. The company had to reset the business with lower prices and more advertising. It took many years for the company to regain its lost position. If the corporate executives and board had probed into the unit’s sources of profit expansion, they likely would have taken corrective action earlier. This example also speaks to the obligation of management and boards to challenge high-performing units as much as they challenge those that are troubled.

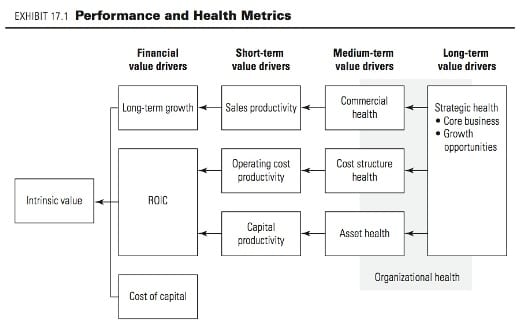

Good performance measurement can help overcome the short- term bias of financial measures by explicitly monitoring how well a company or business unit is positioned to sustain and improve its financial performance. This is what we call a business’s health, and related metrics explain how financial results were achieved and provide causal insights into future performance potential. An example of systematically measuring both performance and health is illustrated in Exhibit 17.1.

The left-hand side of the exhibit shows the financial drivers of value: revenue growth and ROIC. Companies also need metrics that indicate the short-, medium-, and long-term health of the business, as shown to the right of the financial metrics. While every business needs some metrics tailoring, the eight generic categories presented in Exhibit 17.1 can be used as a starting point to ensure that a company systematically manages all the important areas.

Short-term value drivers are the immediate levers of ROIC and growth. They indicate whether current growth and ROIC can be sustained, will improve, or will decline in the near future. They might include sales productivity metrics such as market share, the company’s ability to charge premium prices relative to peers, or sales force productivity. Operating-cost productivity metrics might include the component costs for building an automobile or delivering a package, the rates of rework, and so forth.

Medium-term value drivers look forward to indicate whether a company can maintain and improve its revenue growth and ROIC over the next one to five years (or longer for companies, such as pharmaceutical manufacturers, that have long product cycles). These metrics may be harder to quantify than short-term measures and are more likely to be measured annually or over even longer periods.

Medium-term commercial health metrics indicate whether the company can sustain or improve its current revenue growth, including the company’s product pipeline, brand strength measures, and customer satisfaction. Cost structure metrics measure a company’s ability to manage its costs relative to competitors over three to five years. These metrics might include assessments of continuous improvement programs or other efforts to maintain a cost advantage relative to competitors. Asset health measures might show how well a company maintains its assets and consistently improves asset productivity. For example, a hotel or restaurant chain might measure the average time between remodeling projects as an important driver of health.

Metrics for long-term strategic health include a company’s progress in identifying and exploiting new growth areas and the company’s ability to sustain its competitive advantages against threats. Long- term strategic health metrics might be more qualitative than short- and medium-term metrics, and might be more along the lines of assessments of the company’s ability to deal with changes in the environment. Some examples include new technologies, changes in customer preferences, new ways of serving customers, and disruptive threats.

The final category is organizational health, which measures whether the company has the people, skills, and culture to sustain and improve its performance. As with the other measures, what is important varies by industry. One dimension of this is the needed flows of talent. Pharmaceutical companies have long needed deep scientific-innovation leadership capabilities but relatively few general managers. This may change with trends like the proliferation of personalized therapeutics into product markets. Retailers historically need trained stored managers, a few great merchandisers, and, in most cases, store staff with a customer service orientation.

This framework shares some elements with the balanced scorecard concept that was introduced in a seminal 1992 Harvard Business Review article, The Balanced Scorecard: Measures That Drive Performance, by Robert Kaplan and David Norton. Numerous organizations have subsequently advocated and implemented the balanced scorecard idea. Kaplan and Norton point out that customer satisfaction, internal business processes, learning, and revenue growth are important drivers of long-term performance.

Although our concept of health metrics resembles Kaplan and Norton’s nonfinancial metrics, we don’t advocate their off-the-shelf application. We advocate that companies choose their own set of metrics tailored to their industries and strategies. For example, product innovation may be important to companies in one industry, while in another, tight cost control and customer service may matter more. Similarly, an individual company (or business unit) will have different value drivers at different points in its life cycle.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher John Wiley & Sons, Inc from Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance by Tim Koller, Richard Dobbs, and Bill Huyett. Copyright (c) 2011.

About the Authors

McKinsey & Company is a global management consulting firm that helps leading private, public, and social-sector organizations make distinctive, lasting, and substantial performance improvements. With consultants deployed from more than 90 offices in over fifty countries, McKinsey advises companies on strategic, operational, organizational, financial, and technological issues.